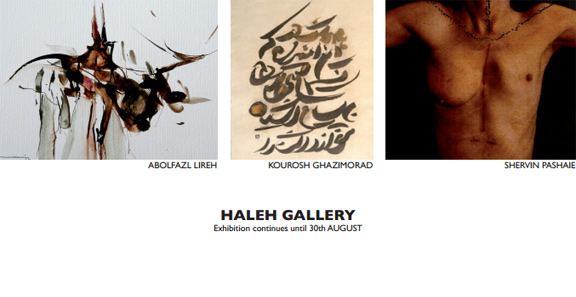

“Movement” by Abolfazl Lireh, Kourosh Ghazimorad & Shervin Pashaie

Why does someone write? Maybe to capture and conserve the fleeting things. Maybe to give his innermost self a home that can be shared with others. Writing down the world, writing yourself into the world are initial impulses that give rise to literature, but also to drawing and painting. Long before Western artists started experimenting with the merging of text and image at the beginning of Modernism, the aniconism of Islamic art had led to the discovery of writing as an aesthetic medium. Movement builds a bridge between Oriental tradition and Occidental present: With Aboulfazl Lireh, Kourosh Ghazimorad and Shervin Pashaie the exhibition gathers three contemporary positions from Iran that originate from the gesture of writing and explore its expressive power, but also its current political impact.

–

Aboulfazl Lirehʼs dancing forms lead us to the common source of writing and painting. The darkly floating, circling smears of Indian ink he drags over the paper with a metal pen are traces of a basic gesture: a nervous motion that catches the colour and chases it across the surface. A dot becomes a line, a wave. Inspiration by musical tunes plays a major role in Lirehʼs work and leads to melodiously swinging compositions. They visualise bodily action with an immediateness that recalls the surrealist écriture automatique: a technique of hasty, associative writing that was meant to outwit rational control and to open the free stream of thought to the unconscious and accidental. Like the all-over patterns of the German Informel or the American action painters who followed the surrealist principle of „automatic“ creation, also Lirehʼs black-and-brown-coloured swirls record the spontaneity and celerity of the painting process and make them traceable for the viewer. Simultaneously, however, Lireh foils the dynamism by placing static structures as barriers into it – rigid bars and grids that block the gliding eye and dam up the flow of painting. The disciplining machinery stands ready, the unconditional freedom of expression remains vulnerable.

The tension between formal restriction and unfolding also charaterises Kourosh Ghazimoradʼs letter- pictures on plain white paper or canvas that focus on the pure, graphic presence of writing. Calligraphic painting has a long history in Islamic culture. Here, the religious prescription of figuative images promoted a very diligent and creative design of the written language. Particularly the texts of the classical Persian poets like Hafez or Ferdowsi – whose works had been introduced to the German audience with the adaptions by Friedrich Rückert and Goetheʼs West-Eastern Divan – were popular since the Middle Ages.In contrast, it was only at the turn from the 19th to the 20th century that Western art began using letters and texts as visual elements – first in literature, like in Mallarméʼs late poems, Marinettiʼs Futurist manifestos or Apollinaireʼs Calligrammes, later also in painting, as in Kurt Schwittersʼ MERZ pictures or in the newspaper fragments of the Cubist collage. Ghazimorad explicitly refers to the centuries-old Iranian tradition of calligraphy, but confronts it with a modern, contemporary approach. With him, the meditative, even sacral act of writing becomes an expressive action that liberates the written word from its signifying function and draws attention from its meaning to its specific pictorial qualities. The signs Ghazimorad condenses into ornamental textures like tightly woven carpets, abstracted to the limits of legibility, signify nothing but themselves. Thus, to someone unfamiliar with the Persian alphabet, they are unreadable in a double sense. They remain accessible, however, through the channel of aesthetic experience: not as writings, but as images.

Shervin Pashaie more openly draws from the pictorial inventory of Western art. His digitally generated and mounted tableaux bring to mind the dark-hued elegance of the Old Masters, of blurred, faded photographs or bleached-out advertisement that has fallen out of time. On the other hand, naked female bodies, as metaphors of purity and beauty, refer to the love symbolism of Persian poetry. At a second glance, Pashaieʼs motifs shift towards a more discomforting dimension: What might have appeared to be the corpus of a Saint Sebastian first, proves to be a hermaphrodite with a male and a female breast. Female torsos are beheaded by image borders. And in the portraits, we meet with empty faces, terrifyingly blinded and erased except for their small, silent lips. Everything personal, individual, human has been robbed from Pashaieʼs monstrously fragmented creatures. Instead, filigree black Farsi characters have been layed upon their bodies – and again, doubt arises: Are the ornamental tattoos not rather brands burnt into the skin, like the ones cattle, but also prisoners and detainees are marked with as signs of possession, submisson or humiliation? Is the chain of letters running across the forehead not rather a badly healed wound? The delicately trickling necklace of words not rather a precise dissection cut? It is not by accident that writing can be both: a decorative accessory – or a razor-sharp instrument that gets under your skin.